History of the DSM

Many people will not realise the history of ‘gender identity’ in terms of how psychology has approached this in both the US and the UK. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (the DSM) is the key resource used to classify mental disorders in the US. There have now been 5 editions of this manual and the changes made between DSM-3 and DSM-5 with regards to approaching ‘gender identity’ have proved highly controversial among many psychologists.

According to the American Psychiatric Association, ‘It was not until 1980 with the publication of DSM–3 that the diagnosis ‘transsexualism’ first appeared. In 1990, the World Health Organisation followed suit and included this diagnosis in ICD-10 [the International Classification of Diseases manual used in the UK]. With the release of DSM–4 in 1994, ‘transsexualism’ was replaced with ‘gender identity disorder in adults and adolescence’.

Further to this, when the DSM-5 was released in 2013, this classification changed from ‘gender identity disorder’ to simply ‘gender dysphoria’. This meant that feeling estranged from one’s sex was no longer described as a disorder, but simply a type of body dysmorphia that—unlike other body dysmorphias—should, for some reason, be validated and affirmed by the clinician. Considering that the rise of gender identity has been predominately a language-based takeover, it is unsurprising that the meanings of words have been adapted in this way to try to shape reality. However, it is shocking that senior leaders in mental health have allowed this to happen without any evidence supporting the belief that one could be born in the wrong sex. In the current DSM - the 2013 DSM-5 - ‘gender dysphoria’ has been explicitly described as needing to be affirmed in patients with ‘psychiatric, medical and surgical treatments’. Rather than being grounded in evidence of beneficial outcomes for patients, this approach seems driven by some contributors’ political will to affirm ‘gender identities’ that differ from patients’ biological sex, despite the potential for future harm and regret.

The DSM-5 Working Groups

The members of the various working groups involved in deciding the content of this latest version of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (the 2013 DSM-5) are listed in Kenneth Zucker’s article here (and below). While Zucker took the lead role of Chair of the DSM-5 Work Group on Sexual and Gender Identity Disorders, the subgroups included those involved in producing the manual’s content on Sexual Dysfunctions, Paraphilias and Gender Identity Disorders.

Paraphilias

The Chair of the Paraphilias Subgroup for the DSM-5 was Ray Blanchard. In the previous edition of the manual, DSM-4-TR, one of the paraphilias was listed as Transvestic Fetishism. In the DSM-5, this was changed to Transvestic Disorder, distancing it from the association with fetishism. The requirement to be considered to have a paraphilia back in the DSM-4-TR was also much easier to fulfil, being ‘likely to cause problems for the individual (i.e., the person has acted on those urges or the urges, or their sexual fantasies have caused marked distress or interpersonal difficulty for them)’. By the DSM-5, the individual would need to fulfil the following to be considered to have a paraphilic disorder; they must ‘feel personal distress about their interest, not merely distress resulting from society’s disapproval; or have a sexual desire or behaviour that involves another person’s psychological distress, injury or death, or a desire for sexual behaviours involving unwilling persons or persons unable to give legal consent’.

By raising the bar for what qualifies as a paraphilic disorder, the latest DSM version may have become overly permissive toward atypical sexual behaviors that can cause psychological harm to those around the individual. As observed in the Aggression and Violent Behaviour Review Journal, ‘This move can be seen as an attempt to ‘depathologise’ milder, ostensibly harmless sexual deviations, while recognising that severe paraphilias, that cause distress, or cause the individual to do harm to others, can be validly regarded as disorders. This change in viewpoint [would] be reflected in DSM-5 by adding ‘Disorder’ to each of the paraphilic criteria in the [previous] DSM (i.e., Paedophilia would become Paedophilic Disorder, while Transvestic Fetishism would become Transvestic Disorder). However, this change could actually dramatically loosen the criteria for paraphilias and may make the criteria more directly dependent on cultural values (Singy, 2010)’.

By downgrading the requirements for these sexual behaviours to be considered problematic, the American Psychiatric Association has implied (intentionally or not) that the element of taboo should be removed from them. This is clearly detrimental to society and encourages the idea that elements of these sexual behaviours are just normal variations and should be socially acceptable.

Interestingly, the DSM-4 also limited the diagnosis of Transvestic Fetishism to heterosexual males, whereas the DSM-5 opens the diagnosis of Transvestic Disorder to females and homosexual males (although the numbers of diagnosed individuals in each of these categories would be intriguing to know).

By diluting the approach to sexually motivated transvestism in heterosexual males, some mental health professionals have raised concerns that this means that behaviour which is potentially dangerous to others could go unchecked and escalate, considering that paraphilias can often coexist. However, as in this article, the focus is sometimes only put on any increased risk of distress to the individual with multiple paraphilias rather than those around them. The individual’s sexual desires are centred, while the lack of consent and potential vulnerability of those around them do not seem to be considered important at all. As described, Transvestic Disorder can often coexist alongside ‘fetishistic disorder, exhibitionistic disorder and voyeuristic disorder’, which would clearly mean that others would be affected when the individual demonstrates these behaviours.

It should also be noted that the discredited organisation WPATH (the World Professional Association for Transgender Health) gave recommendations for the changes to the diagnoses for Gender Identity Disorder and Transvestic Disorder in the DSM-5.

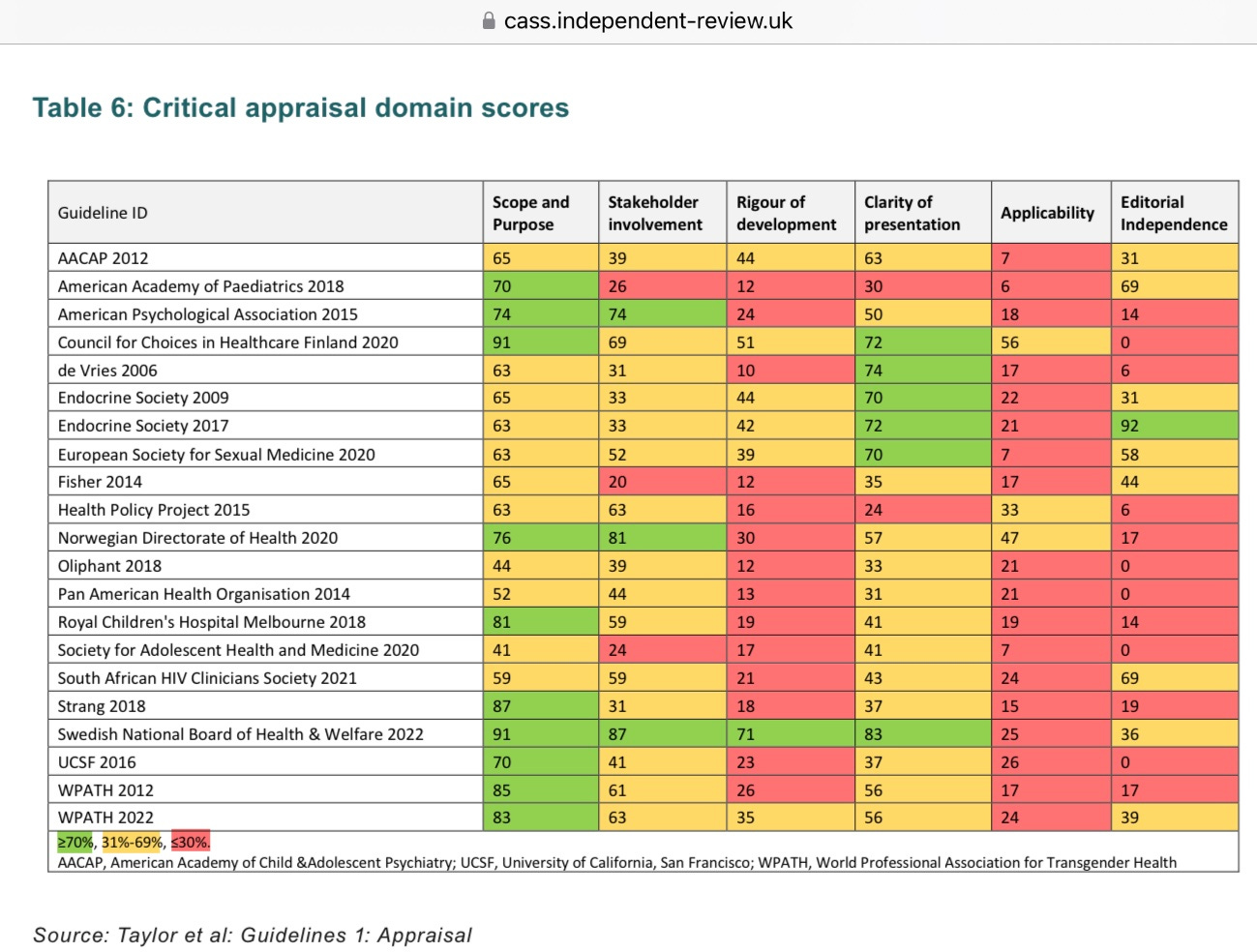

Given more recent revelations about WPATH advising on legislation around gender identity based on little to no evidence, this background of the DSM-5 is alarming. Meanwhile, Kenneth Zucker (who, as previously mentioned, was Chair of the DSM-5 Work Group on Sexual and Gender Identity Disorders) also helped to write version 7 of the “standards of care” guidelines for the World Professional Association for Transgender Health, which the Cass Review described as ‘[lacking] developmental rigour and transparency’. Cass also described how ‘for many [gender identity] guidelines it was difficult to detect what evidence had been reviewed and how this informed development of the recommendations’. In addition, Cass highlighted the circular nature of guidelines such as WPATH’s referencing one another to make it ‘[appear that] there was a consensus on key areas of practice despite the evidence being poor’.

In Jesse Singal’s 2016 article How the Fight Over Transgender Kids Got A Leading Sex Researcher Fired, he describes WPATH’s Standards of Care as ‘one of the bibles for clinicians who treat transgender and gender-dysphoric patients’, which seems fitting now that we know that these Standards of Care were based more on faith in ‘gender identity’ than evidence. Considering WPATH’s now evident lack of credibility, we must ask whether mental health professionals should still be relying upon the definitions that WPATH contributed to in the latest Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (the DSM-5) or whether this should be consigned to history and replaced with standards that truly prioritise the wellbeing of both the patient and society.