The Stain

An attempt at character assassination inadvertently reveals the extent of academic corruption around the issue of 'trans healthcare'

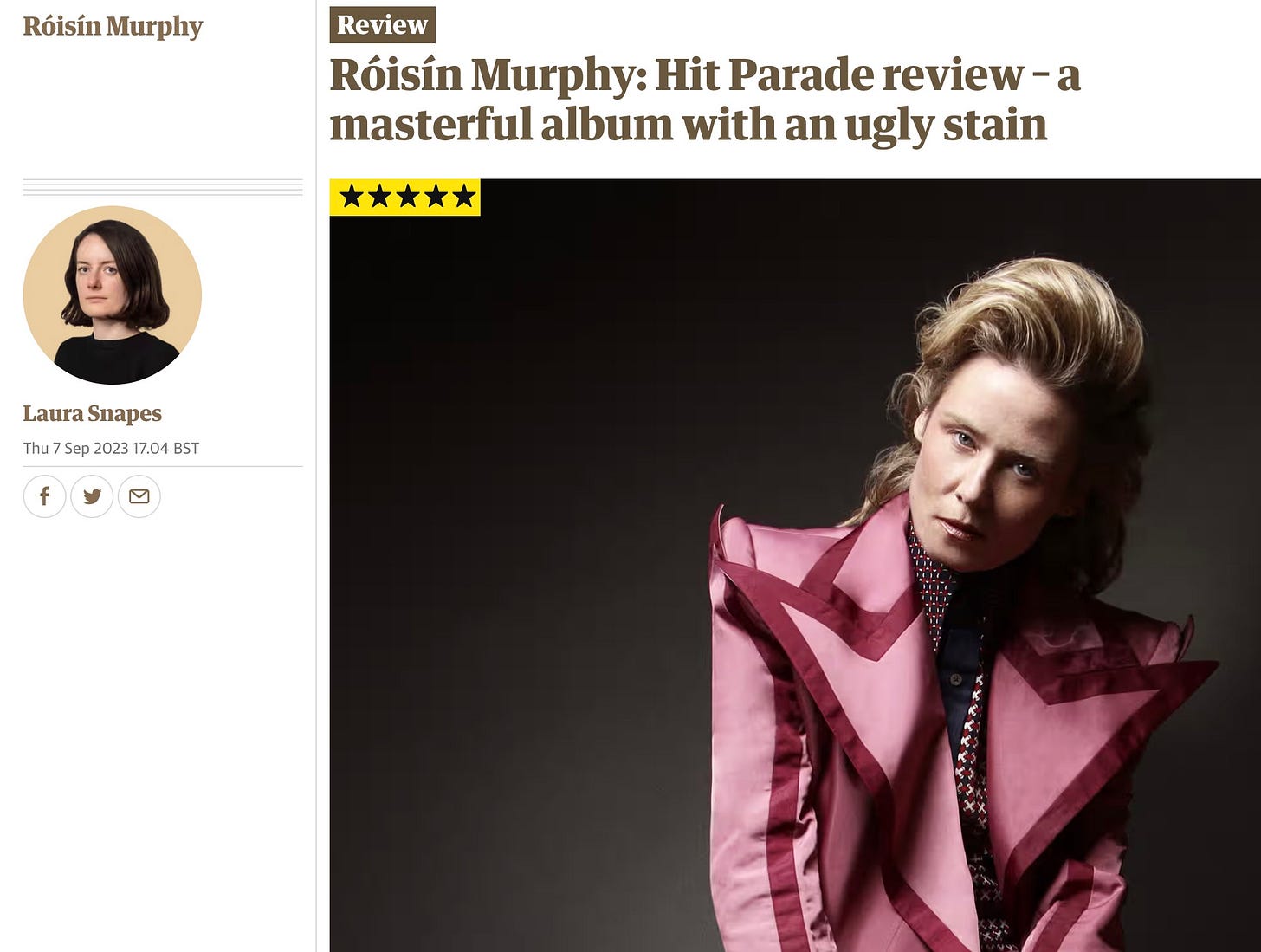

The Guardian’s review of Roisin Murphy’s Hit Parade wasn’t just an ugly stain on the craft of music journalism. There was something even worse than the grudging praise that failed to hide a calculated attempt at character assassination. It was in its false reporting of a study on mental health outcomes for children and young adults treated with puberty-blocking drugs and opposite-sex hormones that the stain seeped through the Arts pages and infected the title’s Science and Health sections too.

The paper helpfully provided the link to the source of the extraordinary claim that “young trans people who can access puberty blockers experience a decrease in depression and a 73% reduction in the risk of suicide,” enabling readers more attentive than the paper’s editor to spot that the study did not in fact discuss suicide, but instead measured suicidal ideation, which in most cases does not lead to suicide. Every suicide is a tragedy, but when you consider that 4 out of 15,000 patients who were receiving treatment or on the waiting list of GIDS were known or suspected to have died by suicide between 2010 and 2020, the most up-to-date research seems to suggest that gender-related distress has a suicide rate of 0.03% which is in keeping with any group of young people with mental health challenges.

The Guardian has since updated the article, but how many people will have already read the original and walked away with a wholly misguided impression of suicide risk among children and young adults who identify as transgender or non-binary? How many children and young adults might believe themselves to be at greater risk of suicide? That the Guardian allowed such a wildly inaccurate statement about suicide to be published suggests that the title has abandoned all commitment to journalistic integrity.

So now it’s my turn to do a review, but this time, of the study that gave us that 73% figure.

Let’s start with the introduction, which is meant to be a summation of the research to date on this topic and how the current study adds to that body of knowledge. The authors state that research in this area supports the claim that ‘medical gender-affirming interventions’ are associated with a decrease in depression, anxiety and other poor mental health outcomes. They provide a number of sources, the first of which is a study by Chew et al (2018). Here is the conclusion:

“Low-quality evidence suggests that hormonal treatments for transgender adolescents can achieve their intended physical effects, but evidence regarding their psychosocial and cognitive impact are generally lacking. Future research to address these knowledge gaps and improve understanding of the long-term effects of these treatments is required.”

In other words, medical interventions change your body, but there's scant proof they enhance your psychological well-being. The second study, by de Vries et al (2014), centres on a cohort of 55 participants who had undergone medical transition starting with puberty blockers, followed by opposite-sex hormones, and finally surgery. They were assessed for psychological functioning and well-being before each of the drug interventions, but crucially, the authors state that the last assessment was ‘at least one year’ after surgery, and that the mean age at this final assessment was 20.7 years. One young person from this study died as a direct result of the complications that arose after the surgery.

Putting all of this together, we are looking at a cohort that began identifying as transgender while still children, who would not have experienced the cognitive development brought on by puberty and who necessarily had surgery while barely into adulthood, if not sooner. And on the basis of their psychological state as little as one year after surgery, the authors were confident enough to assert the following:

“A clinical protocol of a multidisciplinary team with mental health professionals, physicians, and surgeons, including puberty suppression, followed by cross-sex hormones and gender reassignment surgery, provides gender dysphoric youth who seek gender reassignment from early puberty on, the opportunity to develop into well-functioning young adults.”

Does it? There is simply no basis for the conclusion that how young adults feel about medical transition in the short term is going to endure for the rest of their adulthood, which they have only just begun. According to Lisa Littman’s 2021 study of the experiences of 100 young adults who detransitioned, the mean age at detransition was 23.6 years old for females and 32.7 for males, several years older than the cohort in the de Vries study.

Onto the third source, an earlier study by de Vries et al (2011). Take a look at the summary of results:

“Behavioural and emotional problems and depressive symptoms decreased, while general functioning improved significantly during puberty suppression. Feelings of anxiety and anger did not change between T0 [baseline assessment before puberty blockers] and T1 [second assessment after puberty blockers]. While changes over time were equal for both sexes, compared with natal males, natal females were older when they started puberty suppression and showed more problem behaviour at both T0 and T1. Gender dysphoria and body satisfaction did not change between T0 and T1. No adolescent withdrew from puberty suppression, and all started cross-sex hormone treatment, the first step of actual gender reassignment.”

In other words, there were some improvements over time, but even though their puberty was blocked, their feelings of gender dysphoria remained. What the researchers could have done in order to contribute more robustly to the evidence base would have been to find an equally troubled cohort who did not receive medical treatment (what is known as a control group), and then compare outcomes. We’ll never know if the positive changes in behavioural and emotional problems, depressive symptoms and general functioning were due to time or to the suppression of puberty. However, that didn’t stop the researchers from concluding:

“Puberty suppression may be considered a valuable contribution in the clinical management of gender dysphoria in adolescents.”

This contradicts their own findings that puberty suppression had no impact on dysphoria.

The authors then cite the study by Turban et al (2020) that says that puberty suppression is linked with lower lifetime suicidal ideation, and therefore puberty blockers are associated with favourable mental health outcomes. Fortunately, Dr. Michael Biggs has already torn the Turban paper apart here. His criticisms include the sample, which would have necessarily excluded anyone who had detransitioned or desisted, the confounding factor of pre-existing poor mental health in some cases, as well as confusion over whether participants were being asked about puberty blockers or opposite-sex hormones. Biggs concludes:

“The article therefore provided no evidence to support the recommendation “for this treatment to be made available for transgender adolescents who want it” (Turban et al., 2020, p. 7).”

And finally (for now) the authors cite a study by Edwards-Leeper et al (2017) that concludes with the recommendation to begin medical transition for children sooner rather than later. From the abstract alone, we can see that the authors are claiming more than is justified by their findings. This was not a before/after treatment comparison study, but rather a snapshot of the mental health of a sample of patients from the first interdisciplinary paediatric gender clinic in the USA. They found that older patients were more distressed than younger patients, which they used as justification for early medical transition. The problem here is that the authors only see causality as running in one direction, that distress is caused by being a transgender person who is unable to transition, disregarding the possibility that the distress these individuals experience might be what drives them towards a transgender identity. The authors of the Tordoff study make a similar error, claiming that trans and non-binary identifying youth have poor mental health outcomes as a result of the stigma and discrimination towards ‘transgender people’, rather than considering the possibility that those with poor mental health might be more likely to identify as transgender. In both cases, trauma, sexual abuse, discomfort with one’s emerging sexual orientation, or even other mental health conditions could be driving both the distress and the transgender identification. Failing to consider a third factor means that clinicians will be treating a symptom of distress, rather than the cause, with profound and irreversible changes to these children’s bodies.

Knowing how best to treat these individuals depends entirely on understanding the relationship between their distress and their belief that they are transgender or non-binary. Yet the authors adopt a single explanation for this distress, and as a result, only a single solution.

I thought I could sum up everything that is wrong with this study in a tidy 1,000 words, but the more I dig into the citations, the more I find how poor the evidence in favour of tampering with puberty really is, and how often the authors make claims that are simply aren’t true.

Any A-level psychology student worth their salt would be able to tell you that these studies ignore confounding variables, such as pre-existing mental health problems influencing outcomes; they often fail to have a control group for comparison purposes; and they confuse correlation with causation at every turn, with their conclusions always the same – transphobia is to blame, and the only solution is for children and young adults to medically transition as soon as possible.

We should congratulate Roisin Murphy not just for the glowing reviews she's receiving for her music, but for inadvertently revealing the scale of ideological corruption in academic research. And before the Guardian attempts to clean up the flaws they perceive on the conscience of others, they might look at how their standards have slipped to allow such a stain from the music review section to darken its pages and its reputation.

The Guardian was once teased for its typos - hence the friendly knickname 'Grauniad' as used in the late 20th century. Affection for a once great newspaper has evaporated. Those typos, instead of being spelling errors, have become egregious inaccuracies. The Guardian, in print and on-line, is now notorious for its corrupted and incompetent journalism - its much limited readership residing in an echo chamber.

This is bloody marvellous, agreed with every word! Thank you Kathryn